Picking Up Where We Left Off

In the previous part of this series, we explored installing Elixir and Erlang, played around with the interactive shell (iex), and experimented with some of the primitive data types. Getting up and running with Elixir is a breeze.

Now it’s time to actually start writing some real code. And that begins with understanding Elixir’s general program structure.

The Shape of an Elixir Program

Being a functional language, Elixir relies primarily on the use of functions. A typical Elixir program consists of many small functions. At its core, Elixir code lives inside modules. A module is a collection of functions. Think of modules like containers for functions or namespaces. If you’ve worked with Java or C#, you can think of them like classes (though Elixir doesn’t have objects in the traditional sense). So, that is probably a bad comparison. You should get the idea once we start looking at examples.

Speaking of examples, here’s the simplest example I could think of:

defmodule Hello do

def world do

“Hello, world!”

end

endThat’s it. In Elixir, modules are created using the defmodule macro, and by convention module names must begin with an uppercase letter. Inside those modules, functions are defined with the def macro, and their names start with a lowercase letter or an underscore. This simple structure gives Elixir programs a clean, consistent flow that’s easy to read and reason about.

To try out our newly created module:

Save it in a file hello.ex.

Open iex and compile it:

iex(1)> c(”hello.ex”)

[Hello]

iex(2)> Hello.world()

“Hello, world!”A couple of things stood out to me while researching and writing out this:

No return keyword. Functions just return the last value automatically.

No parentheses if you don’t want them. I can call Hello.world without the () if the function takes no arguments.

Functions must belong to a module. In Elixir, every function definition lives inside some module — there are no free-floating top-level functions.

Elixir’s standard library also comes with many useful modules. One of the first you’ll likely encounter as a beginner is the IO module. Elixir’s IO module provides functions for basic input/output functionality for your programs. For example, you can write the de facto first program that everyone writes with:

iex> IO.puts(”Hello, World!”)

Hello, World!

:okHere we use the IO module and the puts function to send text to standard output. The code evaluates the string, prints it to the terminal, and then returns the atom :ok as a result. This is typical of Elixir’s design, where functions both perform a side effect (in this case writing to the console) and also return a value you can use programmatically.

The Pipe Operator

One of the most elegant features in Elixir is the pipe operator, |>. The pipe operator allows you to take the result of one expression and pass it as the first argument to the next function. This makes chains of transformations read like a sequence of steps and avoids deeply nested function calls.

For example:

iex> “ hello world “

|> String.trim()

|> String.upcase()

|> String.replace(”WORLD”, “Elixir”)

“HELLO ELIXIR”Without the pipe operator, you would need to write:

iex> String.replace(String.upcase(String.trim(” hello world “)), “WORLD”, “Elixir”)

“HELLO ELIXIR”The pipe makes the intention much clearer. It reads as: trim the string, uppercase it, then replace a word. This functional style of chaining small functions together is idiomatic in Elixir and one of the reasons code often feels readable and expressive.

Pattern Matching

Elixir’s pattern matching is one of the features that made the language stick out to me when I was researching different functional languages to dive into. If you are new to the language, think of it as a way to de-structure and match data by shape rather than simply assigning variables. It is an important concept to learn when diving into this language.

In Elixir, = isn’t “assign this value to that variable.” It’s “try to match the shape on the left with the value on the right.” This is why = is called the match operator in Elixir.

Example with tuples:

iex> {a, b} = {1, 2}

{1, 2}

iex> a

1

iex> b

2That’s neat. But where it gets interesting is when the match fails:

iex> {a, b} = {1, 2, 3}

** (MatchError) no match of right hand side value: {1, 2, 3}The shapes of the data on both sides don’t line up, so Elixir throws an error.

Pattern Matching in Lists

Lists (and functions, but we aren’t there yet) are where pattern matching gets really powerful.

iex> [head | tail] = [1, 2, 3, 4]

[1, 2, 3, 4]

iex> head

1

iex> tail

[2, 3, 4]That syntax [head | tail] means: take the first element and call it head, then bind the rest of the list to tail. Note: you don’t have to use the phrase “heads” or “tails” but this is the examples that I came across. You can name those two whatever you would like, but it doesn’t change the outcome of the statement. The first term will always be matched to the first element of the list and the rest of the list will be matched to the second term.

Pattern Matching in Function Heads

This one blew my mind. You can write multiple definitions of a function that behave differently depending on the shape of the input. This is where I started to become enamored with the language.

defmodule Math do

def describe({:ok, value}), do: “We got a value: #{value}”

def describe(:error), do: “Something went wrong”

endTry it:

iex> Math.describe({:ok, 42})

“We got a value: 42”

iex> Math.describe(:error)

“Something went wrong”That’s not if/else. That’s pattern matching at the function level.

Exploring More of Elixir’s Core Data Types

Before we go too far, let’s pause and really get to know some of Elixir’s core data types.

Atoms

Atoms are constants where the name is the value. If you’re familiar with Ruby, they’re kind of like symbols, or if you are familiar with C/C++ they are kind of like enumerations.

iex> :hello

:hello

iex> :world == :world

trueAtoms are used everywhere in Elixir, especially to signal status (: ok, :error). Atoms are always prefixed with a colon and are followed by some combination of letters, numbers, and/or underscores.

Another interesting quirk in Elixir is that there’s no separate boolean type. Instead, true and false are just atoms under the hood - :true and :false. And to make life easier, the language lets you use them without the colon, so you can simply write true and false like you would in most other languages. This confused me while I was reading through documentation.

Numbers

Numbers in Elixir are straightforward.

Integers: unlimited precision. You can do 123456789123456789 * 123456789123456789 and it just works. There is theoretically no upper limit to the size of integers in Elixir.

Floats: will take up either 32 or 64 bits depending on the architecture of the machine it is running on.

iex> 10 / 2

5.0 # notice: division always returns a floatThat last part tripped me up. In Python, 10 / 2 gives 5, an integer. In Elixir, it’s always a float. If you want integer division, you use div/2:

iex> div(10, 2)

5Or remainder:

iex> rem(10, 3)

1Note: You may be wondering what in the word is the phrase “div/2”. Well, that is what is called function arity. Arity describes the number of arguments that a function receives as parameters. In this case, the div function takes 2 arguments in the example. This, mixed with the module and name, is how we identify functions in elixir. You will need to know this once you deep dive into the elixir documentation.

Strings

Strings are UTF-8 binaries. That means you can work with emojis and accented characters, woo!

iex> “hello” <> “ world”

“hello world”

iex> “hełło”

“hełło”Elixir also gives you string interpolation:

iex> name = “Mick”

iex> “Hello, #{name}”

“Hello, Mick”And since strings are binaries, you can even match on them:

iex> “he” <> rest = “hello”

“hello”

iex> rest

“llo”Mini Project: User Profile Formatter

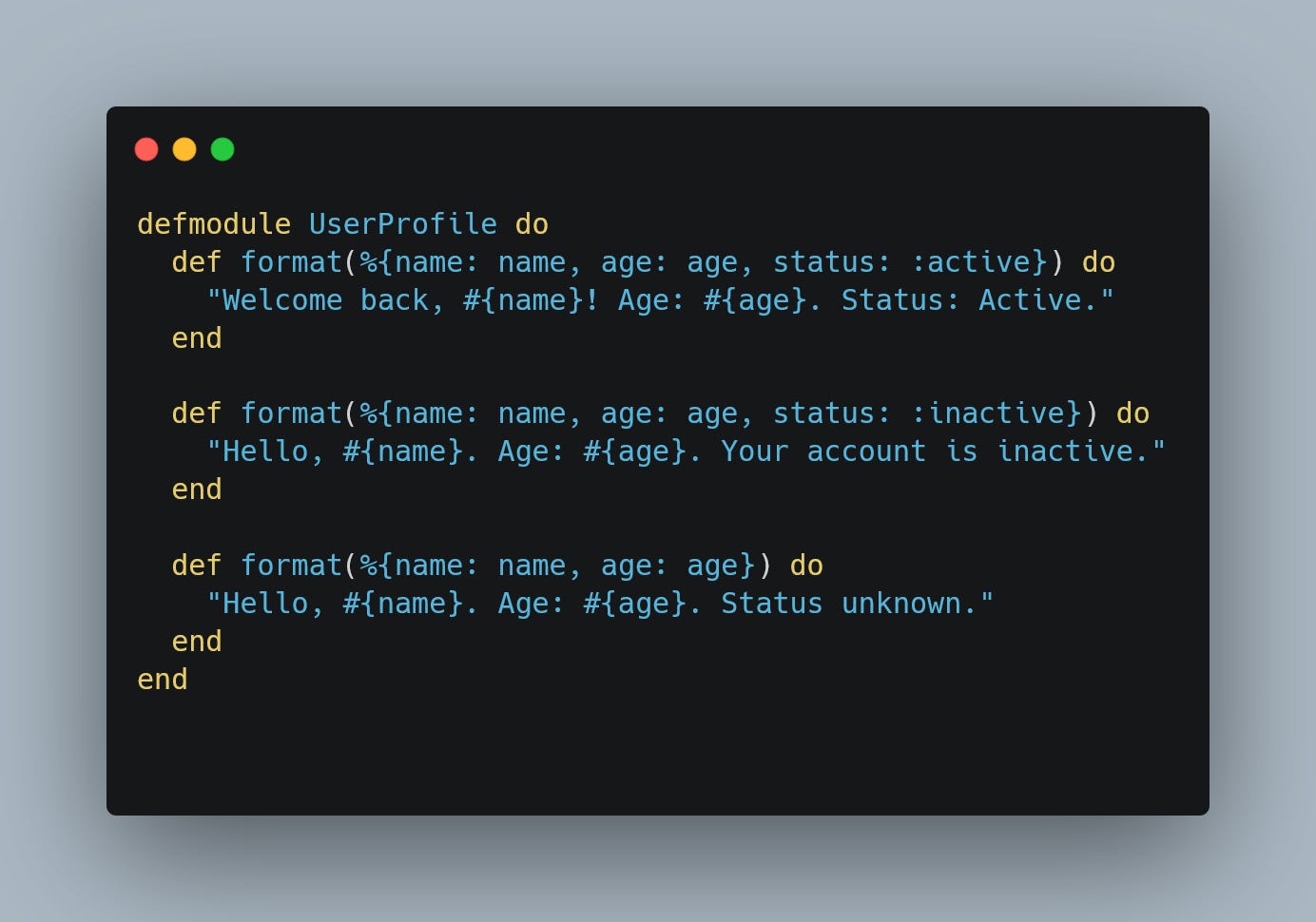

To tie this all together, let’s build a small module that:

Takes a user struct (map) with a name, age, and status.

Uses pattern matching to greet them differently depending on their status.

Demonstrates atoms, strings, and numbers.

defmodule UserProfile do

def format(%{name: name, age: age, status: :active}) do

“Welcome back, #{name}! Age: #{age}. Status: Active.”

end

def format(%{name: name, age: age, status: :inactive}) do

“Hello, #{name}. Age: #{age}. Your account is inactive.”

end

def format(%{name: name, age: age}) do

“Hello, #{name}. Age: #{age}. Status unknown.”

end

endTry it out using the interactive shell:

iex> c(”user_profile.ex”)

[UserProfile]

iex> UserProfile.format(%{name: “Mick”, age: 30, status: :active})

“Welcome back, Mick! Age: 30. Status: Active.”

iex> UserProfile.format(%{name: “Danny Rojas”, age: 25, status: :inactive})

“Hello, Danny Rojas. Age: 25. Your account is inactive.”

iex> UserProfile.format(%{name: “Ted Lasso”, age: 22})

“Hello, Ted Lasso. Age: 22. Status unknown.”This little project shows off almost everything we’ve covered: modules, functions, pattern matching, atoms, numbers, and strings.

Reflection

Writing this little module was where things really started to click for me. I’m beginning to see how the core features of the language fit together — pattern matching makes my code feel natural, and even the basic data types have their own quirks that keep things interesting. It feels like I’m finally starting to think in Elixir rather than just copying examples.

Next, I want to dive into recursion, immutability, and some more of the control features that make functional programming in Elixir so powerful. And honestly, I’ll